Intelligent People Are Easier to Fool Than They Think

When people hear that I’m a mentalist and illusionist, they assume my job is to fool people.

That’s not quite right.

What I’ve learned, after years of working with executives, engineers, founders, and academics, is something more precise—and more useful:

People don’t get misled because they lack intelligence. They get misled because they put their attention in the wrong place.

Under pressure, most people—no matter how smart—operate at one of three levels of understanding. These aren’t fixed types. They’re habits of attention. And the difference between mediocre judgment and exceptional judgment has less to do with IQ than with what someone treats as the point of the situation.

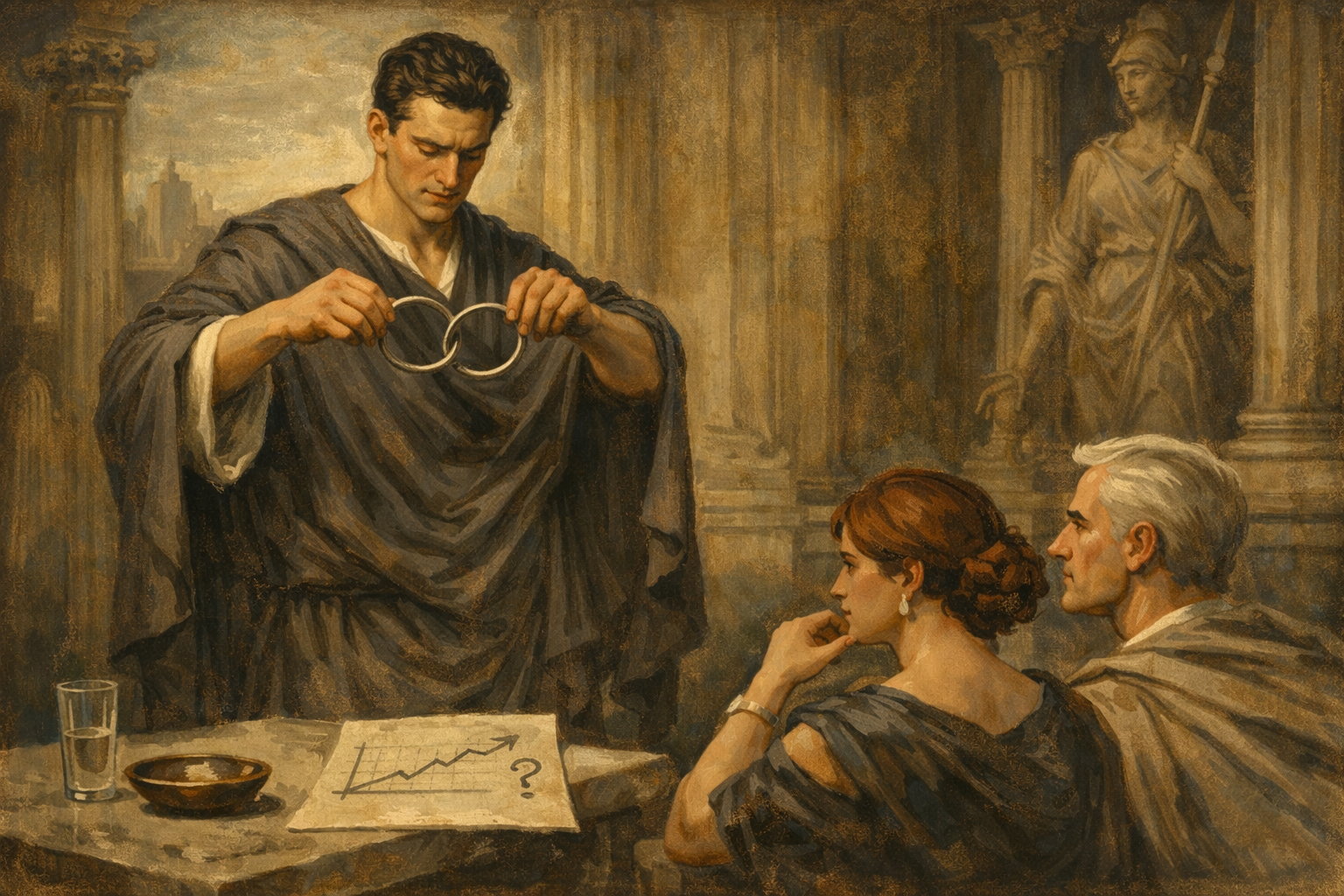

A concrete example: Crazy Man’s Handcuffs

There’s a classic illusion called Crazy Man’s Handcuffs. I learned it years ago from David Copperfield.

Two rubber bands appear to be linked together. Then, impossibly, they melt through each other—right in front of you.

Most magicians present this as a puzzle: Can you catch how it’s done?

I don’t.

I use it as a metaphor for overcoming obstacles—the kind of business or personal obstacles that feel fixed, locked, or immovable until, suddenly, they aren’t.

That message is the point.

The effect exists to carry that point.

The method exists only to make the effect possible.

Just as the point of an iPhone is not its circuitry or operating system, but what those things allow people to do, the point of the illusion is not the trick itself, but what it demonstrates.

The smartest people in the room instinctively understand this.

Three levels of understanding

The same demonstration lands very differently depending on where someone stops thinking.

Level One: Explanation as Defense

At the lowest level, the goal isn’t insight—it’s closure.

Someone notices a small detail and immediately reaches for an explanation that makes the discomfort disappear:

“It’s just sleight of hand.”

That statement may be technically true—and completely beside the point.

In business, this level sounds like:

“People just resist change.”

“That’s how the market works.”

“It was obvious in hindsight.”

These explanations aren’t wrong. They’re irrelevant.

They explain how something happened while refusing to engage with what it means. Once the ego is soothed, thinking stops.

Level Two: Mechanism Obsession

Most intelligent professionals live here.

These are people who notice that something doesn’t add up and can’t let it go. When they watch Crazy Man’s Handcuffs, they may even notice that the rubber bands separate before I say they do.

They don’t dismiss the illusion. They interrogate it.

They ask:

“How did that happen when I was watching so closely?”

This is real intelligence at work—curious, disciplined, unsatisfied with shallow answers.

But there’s a trap.

They assume that how is the right question.

They pursue the missing step inside a frame they’ve already accepted:

This is a trick. There must be a method. Find it.

In organizations, this shows up as:

refining a failing strategy

optimizing a broken process

doubling down on a model that no longer fits reality

They think harder—but about the wrong thing.

Level Three: Oriented Toward the Point

At the highest level, attention goes where it belongs.

These people don’t ignore the method—but they don’t privilege it either. They understand that the mechanics are in service of something else.

They ask:

“What is this actually a demonstration of?”

“Why does this resonate right now?”

“What obstacle am I being invited to re-see?”

They focus on the point, not the plumbing.

This distinction separates clever gadgets from enduring tools—and competent leaders from transformative ones.

One reason Steve Jobs is still studied isn’t that he obsessed over how devices worked.

He obsessed over what they were for.

The technical brilliance followed from that orientation—not the other way around.

The real takeaway

So the claim is not that intelligent people are “easy to fool.”

It’s this:

Anyone with intelligence can make themselves smarter by learning where to place their attention.

Low-level thinkers stop at explanation.

Mid-level thinkers chase mechanism.

High-level thinkers orient toward meaning and purpose.

The goal is not to abandon analysis.

It’s to subordinate it.

Why this is my work

I don’t use illusion to show how clever I am.

I use it to make a point felt, not merely stated—because meaning that is only explained rarely survives pressure.

When people leave one of my performances or sessions, they don’t leave talking about tricks.

They leave talking about:

obstacles they suddenly see differently

assumptions they didn’t know they were carrying

decisions that no longer feel as fixed as they did an hour earlier

That’s not entertainment layered with ideas.

It’s ideas made visible.

And in rooms where decisions actually matter, that difference is everything.